Security Watch

Standards Insecurity

Communications of the ACM, Volume 46,

Number 12 (2003)

Rebecca T.

Mercuri

Communications of the ACM

Vol. 46, No. 12 (December 2003), Pages 21-25

Standards can provide an important component in the computer security

environment but they should not be relied on blindly.

In the computer industry, standards play an important role by enforcing

security baselines and enabling compatibilities among products. In the early

days of computing, lacking common agreements, problems ensued with floating

point configurations, ASCII vs. EBCDIC encoding battles, and little vs. big

endian data mixups. Such issues, especially when they affect data integrity,can

pose a security risk. In the best of worlds, standards provide a neutral ground

where methodologies are established that advance the interests of manufacturers

as well as consumers, while providing assurances of safety and reliability.

At the opposite extreme, standards can be inappropriately employed to favor

some vendors' products over others, make competition costly, and encourage

mediocrity over innovation, all of which can have negative effects on security.

In this column, I consider the current standards environment and offer some

suggestions for its increased understanding and improvement.

A host of computer security standards currently exist, including those for

general use like the Common Criteria and its predecessor TCSEC/ITSEC, and

others specific to the Internet like SSL and PKCS. Standards documents range

from pamphlet-sized to tomes as hefty as the Manhattan phone book. Creation

of a standard can be done in an ad hoc manner, or it may followlengthy (and

even somewhat recursive) procedures using standardized guidelines applied

to the new standard's development. Standards groups can be governmental, non-profit,

volunteer, membership-based, corporate, or a combination of these types.

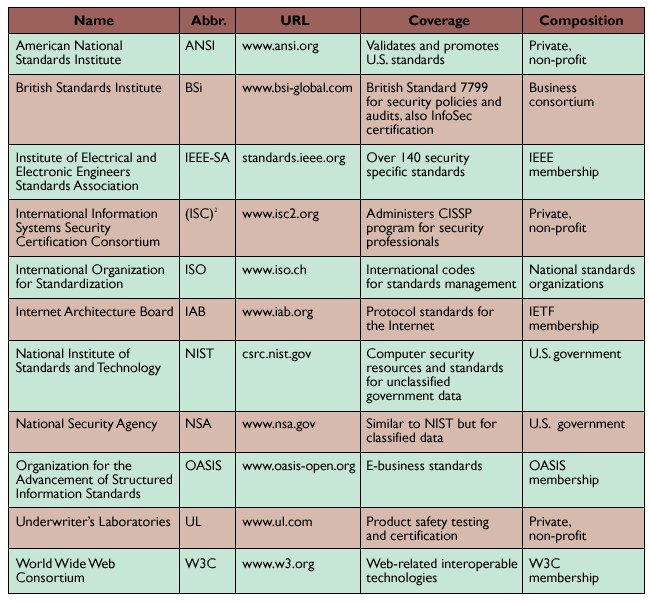

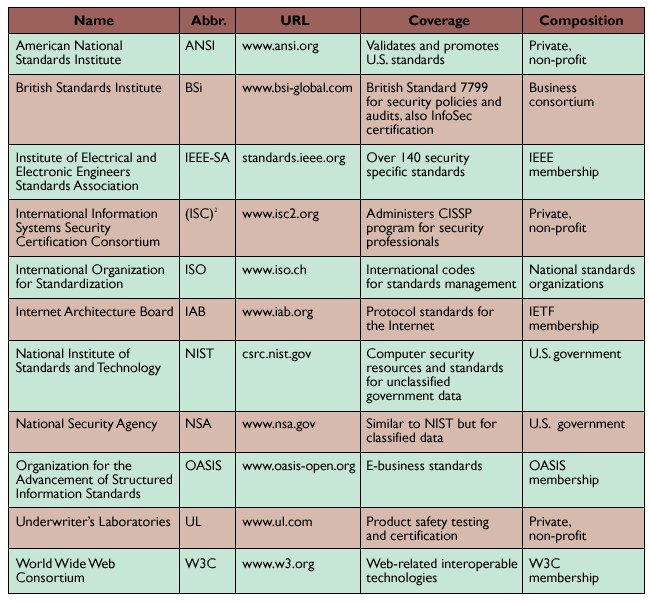

Organizations responsible for creating and maintaining information security

standards form a veritable alphabet soup (see the table here). Although ACM

does not include a chartered standards body, some of its membership overlaps

the 15,000 participants in the IEEE Standards Association, providing input

to the computer-related components of their portfolio of nearly 1,300 existing

or developing standards. As well, ACM members provide valuable contributions

to many of the other standards organizations mentioned here.

The standards industry, such that it is, receives a considerable amount

of money for the services provided. Manufacturers pay agencies various fees

for the testing, record-keeping, auditing, and certification processes performed

on their products. Although government standards can usually be freely obtained

via the Internet, many other standards are the copyrighted properties of their

parent organizations, and documentation must be purchased, some even while

still in draft mode. Manufacturers, inspectors, and systems specifiers may

find it necessary to buy directories from standards bodies in order to locate

certified components and the vendors who can supply them. Because of the

large number of products sold in the global marketplace, certification seems

like a reasonable way to ensure a certain level of quality control, but the

costs and time involved in obtaining it can lock out small companies with

good new ideas, while a status quo from established vendors may be allowed

to prevail.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Even though a standard may have been created

through an open process,

this does not necessarily dictate that the certification process will be

transparent.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

As probably the classic archetype for standards overseers, Underwriter's

Laboratories, Inc. (UL) describes itself as "an independent, not-for-profit

product safety testing and certification organization" that has "held the

undisputed reputation as the leader in U.S. product safety and certification"

since its founding in 1894. UL has developed more than 800 safety standards,

some in conjunction with ANSI (the American National Standards Institute),

the U.S. Department of Defense, and other groups, over a broad range of application

areas (including telecommunications, robotics, and semiconductor fabrication).

In 2002, some 5,900 UL staff members conducted 106,942 evaluations and 555,222

manufacturing process compliance audit visits for over 17 billion products

made by over 66,703 manufacturers worldwide. The simple UL in a circle—the

UL Listing Mark—is its most common insignia, indicating "that samples of this

product met UL's safety requirements." Based on the preceding numbers, though,

it appears that only one in every 159,000 UL-marked products is actually tested

by UL itself.

When a product is granted certification under a particular standard, it

is common to issue a display mark to notify retailers and purchasers of this

fact. Gone are the days when such certification marks were as recognizable

as the UL Listing Mark and the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. Regardless,

obtaining some marks may be necessary in order to compete or even participate

in certain markets. On the bottom of my iMac keyboard, for example, are the

marks CE, FCC, VCCI, C Uus, TUV Rheinland, and a dark dot with a check inside.

A bit further over on my desk, the container holding my blank CD-R discs is

marked Certified Plus with the words compatibility, reliability, and usability

written around a + sign. Do any of these markings imply consumer warranties?

How does one find out? Somehow these insignia don't inspire the blissfully

naive sense of confidence in product safety and quality assurance that the

old UL mark in a circle once did.

As for the UL, it now issues approximately 20 different marks, including

that C Uus one underneath my keyboard, which is its Recognized Component Mark

for parts integrated into larger systems. The UL doesn't provide warranties,

but if you have experienced a problem (say your house burns down because of

a defective computer monitor), you can submit a Consumer Product Report Form.

If you mail the product to UL, it will reimburse your shipping expenses and

even return the item to you after conducting an investigation. The UL does

assist with notification about product recalls, but it is unclear how to

proceed if you hope to recover related damages, or if you believe the actual

UL certification process was somehow flawed.

Even though a standard may have been created through an open process, this

does not necessarily dictate that the certification process will be transparent.

Certifying authorities may develop proprietary sets of testing procedures,

which in turn may generate reports that are not intended to be released for

examination by the purchasers of the certified components. Manufacturers may

choose to protect their products under trade secrecy (in addition to or in

lieu of patents and copyrights), so the issuance of certification may not

reveal much more than an imprimatur of compliance. This is especially true

under the Common Criteria program, where the details pertaining to risks analysis

and mitigation may be buried within proprietary Protection Profile and Target

Of Evaluation documents. Of course, a purchaser may make the revelation of

these documents a requirement of procurement, but this might restrict competitive

bidding, especially if the majority of vendors have decided to shield the

composition of their products behind the certification process.

In the case where certification has various tiers, like the Common Criteria,

it is also important to understand exactly what components have been certified

and at which levels, in order to ascertain whether the intended product application

is appropriate. The sidebar "Understanding Standards" provides a set of questions

that can be useful in sorting through the hodgepodge with vendors and certification

authorities.

As an interesting twist, the mere existence of a standard does not grant

a manufacturer blanket permission to construct a product to those specifications

without running the risk of copyright or patent violations. MPEG is one (albeit

non-security) example where even independent implementation requires negotiation

with patent holders who have contributed technology to the standard. This

standard is owned by the International Organization for Standardization (the

same group that administers the quality management certification programs

known as the ISO 9000 family), and it requires that all the technology within

MPEG be licensable by its contributors on "fair and equal terms." MIT Media

Lab's Eric Scheirer has noted that although this type of policy rewards developers

who hold intellectual property rights, it also discriminates against small

companies and hobbyists who may be unable to afford the licensing fees. As

well, it is imaginable that a standard might be tainted by requiring the inclusion

of a particular component that could inadvertently pose a security risk.

A relatively new player in the standards field is OASIS, "a not-for-profit

global consortium that drives the development, convergence and adoption of

e-business standards." OASIS is composed of Individual, Contributing, and

Sponsoring members, who pay annual fees ranging from $250 to $13,500. Individual

members are allowed to participate fully in Technical Committees (the working

groups that formulate the standards), but are not eligible to vote. OASIS

maintains formal liaisons with many of the other major standards groups, some

of whom are also Sponsoring members, and has created a number of open standards

pertaining to XML and structured information frameworks, including the recently

adopted Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML). The OASIS open standards

policy allows OASIS specifications to be provided on a royalty-free basis

(downloadable at no cost), with all external intellectual property agreed

to be licensable (though not necessarily for free, as in the preceding MPEG

example). It should be noted that all OASIS standards contain a warranty disclaiming

any express or implied fitness of purpose and merchantability.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Although the systems that provide regulatory

and certification controls may seem formidable,

ultimately their administration must be responsive to the marketplace,

or those standards products will not remain viable.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Like OASIS, The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) was created in the mid-1990s

as a membership organization. The cost of membership in this group is a bit

more pricey, with only two classes offered: Full at $57,500 and Affiliate

at $5,750 per year. The group's 380 members comprise a veritable Who's Who

of international Internet industries. The organization provides an informational

forum and produces "interoperable technologies" that include specifications,

guidelines, software, and tools. Active working groups include projects on

accessibility, device independence, quality assurance, and there are useful

FAQs on security and other Web-related topics hosted on the W3C Web site (see

www.w3.org).

One of the W3C's best-known initiatives is its Platform for Privacy Preference

Project (P3P, see www.w3.org/P3P/P3FAQ.html)

spearheaded by AT&T's Lorrie Cranor. P3P was developed as an industry

standard that "enables Web sites to express their privacy practices in a

standard format that can be retrieved automatically and interpreted easily

by user agents." Although well-intentioned, the project is illustrative of

the difficulties encountered in standards creation and deployment. At one

point, a major patent infringement claim resulted in some of the members

removing themselves from the W3C's Working Group. As well, there were P3P-related

concerns in the U.S. regarding whether privacy should be industry-driven

or regulated by legislation, and there was a dispute between the European

Union and the U.S. over transatlantic personal data flow via the P3P protocol.

Even though consensus was eventually developed, critics such as Attorney

Benjamin Wright have claimed that P3P punishes non-compliant Web sites by

blocking or impeding their cookies, and that the encoding of privacy policies

via P3P may not be sufficient to survive a liability challenge in court.

If a company, group, or individual feels that a standard is inappropriate,

there are various ways to make changes. One can work within the standards

framework to try to change or influence policies, but this may be difficult

(if not impossible) for smaller players. Another method is to create an alternative

market environment where the standard is not employed—the open source movement

has been rather successful in this regard. Or the standard can be augmented,

such as Wright did with his DSA code for P3P that attempts to disavow legal

liability for the policy, thus rendering it meaningless. This scheme, as one

might imagine, was met with considerable industry protest. There are also

legal and legislative routes that can be used to either constrain use or

require addenda to an existing standard.

Although the process for certification of a product under the auspices of

a standard is typically well defined, the decertification of a defective product

or standard is often lax. For example, few U.S. citizens realized that all

of the brand-new voting machines deployed in communities for the 2002 elections

were certified under the already-deemed-obsolete 1990 Federal Election Commission

(FEC) inspection guidelines. New standards are not necessarily even required

to comply with current industry practices. The 2002 FEC Voting System Standard

(VSS) contains blanket exemptions for Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) products,

despite complaints from many computer experts who testified that this could

provide a serious security loophole. Recalls are the typical solution offered

when a product malfunctions, and although California's gubernatorial recall

was not motivated by defective voting machines (although the effort to postpone

it was), one can imagine a scenario where an entire election could be recalled

if equipment was subsequently deemed unreliable or if tampering was discovered.

This could create a sense of mistrust in the government or a feeling of disenfranchisement

among the electorate. It is no wonder certain vendors of electronic balloting

devices have encouraged the adoption of standards that allow them to remove

the ability to perform an independent recount that could potentially conflict

with results internally generated by their computer systems. Currently, the

legislative route (mentioned previously) is being used to circumvent some

of these problems by constructing state and federal bill wording that would

require the availability of voter-verified paper ballots that can be used

to provide independent election audits.

As with any other security process, standards must be assessed for their

appropriateness, in both technology and application, prior to as well as during

their use. Computer security standards should be understood as fluid, rather

than static, to best reflect the constantly changing environments in which

they are being deployed. Although the systems that provide regulatory and

certification controls may seem formidable, ultimately their administration

must be responsive to the marketplace, or those standards products will not

remain viable. Since insight on security matters can be derived from the discourse

provided by the standards development process, all levels of participation

are valuable and should continue to be encouraged and open. In these ways,

we can hope to "set the standard" for better standards, now and in the future.

Author

Rebecca Mercuri (Rebecca_Mercuri@ksg.harvard.edu) is a research fellow

in the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Table: Computer security-related standards and certification organizations

Sidebar: Understanding standards

1. What is the overseeing body that controls the standard

and how is it managed?

2. Who were the members of the working group that created

the standard,

how were they selected, and what were

their interests?

3. Does the standard adequately reflect current industry

practices?

4. Which products or product families are subjected to

the standard?

5. How is the standards process applied to the products?

6. What is the meaning of certification under the standard?

7. How are later-discovered defects in the standard mitigated?

8. If the standard has changed, is it possible to differentiate

certified products?

9. What percentage of the products are actually examined

and what is done to ensure

uniformity among products that are

not examined?

10. How are defective products handled?

©2003 ACM 0002-0782/03/1200 $5.00

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for

personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are

not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies

bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise,

to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior

specific permission and/or a fee.

The Digital Library is published by the Association for Computing Machinery.

Copyright © 2003 ACM, Inc.