Nov. 8 — The state of siege caused by this undecided election is all the proof we need that America must find a new way of casting ballots. And that new way should somehow involve the Internet.

OF COURSE, THERE ARE plenty of reasons why voting online isn’t yet ready for primetime. It could provide a field day for teen-age hackers and terrorists, for one thing, and the Internet isn’t yet in every home. But Tuesday night was a reminder that polls (just one scientific notch over a crystal ball) and the current voting systems aren’t necessarily prime-time material, either. While the TV pundits were hoo-hahing, apologizing, and pontificating all over again on Tuesday night — not to mention all day Wednesday — and contemplated the nefarious Palm Beach “butterfly ballot,” visions of voting on the Web have been dancing in my head.

For several hundred military personnel who live around the world, those visions became a reality in the Bush/Gore contest.

A special pilot program allowed members of the military who are registered in five U.S. locations to cast ballots from computers using special, secure software. If you were stationed overseas — and you’d ordinarily vote in Orange or Oskaloosa counties in Florida; Dallas County in Texas; Weber County in Utah; or in South Carolina — you wouldn’t have bothered with paper absentee ballots.

The Federal Voting Assistance Project is a federal program charged with making it clear to Americans living overseas that they understand how to cast ballots and obtain voting information. After the last federal election in 1996, the Project identified the Net as a possible boon to overseas voting.

Then, last December, in a memo titled “Electronic Government,” the White House commissioned a one-year study of the feasibility of Internet voting.

As part of that investigation, just last month, a conference was convened featuring social scientists, government officials, technical people, and others just generally interested in the notion of online voting.

FLORIDA FOIBLES

At the gathering, the event’s Web site shows, the very essence of voting on the Internet was dissected: What would make Net voting safe and secure, would Net voting in fact corrupt democracy, what other problems have been raised by electronic balloting in the past? One notorious Florida case occurred in 1993 when the St. Petersburg mayoral race yielded odd results.

“For an industrial precinct in which there were no registered voters, the vote summary showed 1,429 votes for the incumbent mayor (who incidentally won the election by 1,425 votes),” writes Rebecca Mercuri, then a research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania. “Officials explained under oath that this precinct was used to merge regions counted by the two computer systems, but were unable to identify precisely how the 1,429 vote total was produced. Investigation by the Pinellas Circuit Court revealed sufficient procedural anomalies to authorize a costly manual recount, which certified the results.”

It’s not just computers that have caused issues in ballot counting. The ultra-close 1960 presidential race raised similar questions about the way we vote — but in the phone industry trade publication Telephony, a different household appliance was raised as the solution.

“Contemporary voting machines and paper ballots are about as out-of-date today as the small pellets dropped into the urns of ancient Rome. Yet, the American election system has available — or imminently available — the equipment for allowing each citizen to vote in the privacy of his home, with final returns becoming available a matter of minutes after the closing of the polls,” said the 1961 article.

In 1964, the father of broadcasting himself, David Sarnoff, envisioned a time when Americans didn’t need to leave the house to vote. The Christian Science Monitor reported that the RCA chairman’s vision “would involve television, the computerized telephone, standard and high-speed circuits of regional and national computers.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Of course, that hasn’t happened. But let’s hope on the heels of this election mania that we’ve experienced this time around that something approximating it will. The White House study of online voting and this FVAP experiment are just the beginning; there has got to be a better way for we as a people to come together.

How would you envision it working? Or are you one of those people who favors an old-fashioned ballot process a la the hit summer show “Survivor”?

If you are, you might be interested in reading about the origins of something that’s really old-fashioned: the origins of the electoral college. No discussion of the mechanics of an election in the Internet age would be complete without a quick acknowledgement of the ironies of progress.

One explanation on the Jackson County Missouri election board page: It turns out our forefathers created it to compensate for the fact that they lived in a world where travel and mass communication were hardly the norm, and where politicians didn’t politic — since it was seen as unbecoming. The electoral college procedures, therefore, kept the balance of power out of the hands of the most populous states. Think about it: if there was a direct vote, the guy from Massachusetts would invariably beat the guy from Rhode Island time and again.

That we’re now contemplating votes via a global computer network shows just how much things have changed since then.

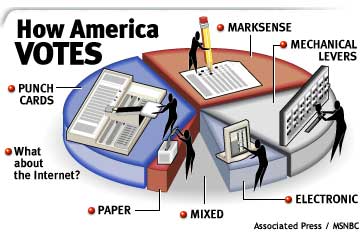

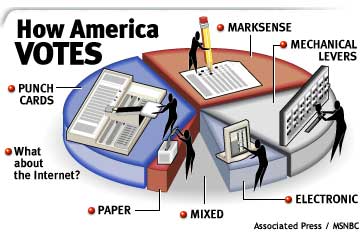

Vote lately? Millions of Americans have, but not everyone used the same system. There are five common voting systems in the country and each has its flaws, according to the Federal Election Commission. Click a slice of the pie chart above to learn more about the different ballot methods. (Clicking doesn't work in this version but the information is below.)

PUNCH CARDS: Used by 37.3 percent of voters in 1996.

How it works: Voters slide a card under a perforated board that displays candidates or measures. Then they use a stylus to punch through appropriate areas on their card. That card is then placed into a sealed box and tallied by machine at the precinct.

Potential flaws: Sometimes tabs, or chads, on the ballot don't completely detach. Handling can cause some chads to unintentionally fall out. Either way, the vote may be invalidated.

PAPER: Used by 1.7 percent of voters in 1996.

How it works: This is as simple as it gets. The candidates and measures are laid out on paper. Voters mark boxes for their choices and then drop the form into a sealed ballot box. Usually, these votes are tallied by hand. Many absentee ballots use this system, along with some small town precincts.

Potential flaws: Historically, this system has fallen victim to ballot box stuffing.

MARKSENSE: Used by 24.6 percent of voters in 1996.

How it works: Familiar to school kids across the country, these ballots require voters to fill in bubbles for their choices. They are rapidly read by computer. Many absentee ballots use this optical scan system.

Potential flaws: The computer reader can easily misread smudges on the ballot or bubbles that are incompletely marked.

ELECTRONIC: Used by 7.7 percent of voters in 1996.

How it works: Officially, these are Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) systems -- the ATM of voting. Choices appear on a monitor and voters press buttons for each option. That information is then stored on disk. Some advocates of this approach say it should be available via the Internet.

Potential flaws: The machines might be vulnerable to hackers by precinct staffers. And what about the computer illiterate? Do they understand how to vote on an electronic ballot box?

MECHANICAL LEVERS: Used by 20.7 percent of voters in 1996.

How it works: Sort of like a voting slot machine -- pull the big arm and see if your candidate wins. Each candidate or measure has its own lever that, when pulled, adds a vote to a mechanical counter. Sound old fashioned? It is. Lever voting machines went out of production years ago.

Potential flaws: Critics charge corrupt election officials or mischievous voters can relabel these machines. One study suggested that descriptions on some levers were too high for short people to read.

MIXED: Some 8 percent of voters used mixed systems in 1996.

How it works: In a few voting districts, budget concerns or technical problems forced precincts to use more than one of the methods above. For instance, many states hold votes for elected officials using mechanical levers, but also distribute paper, punch cards or marksense ballots to provide more information on referendums.

Potential flaws: Critics charge corrupt election officials or mischievous voters can relabel these machines. One study suggested that descriptions on some levers were too high for short people to read.

INTERNET: No one voted via Internet in 1996, though a small pilot program allowed some overseas military personnel to cast absentee ballots that way this year.

How it works: This November, under a program called the Federal Voter Assistance Program, a small number of overseas military personnel were allowed to cast their ballots over the Internet. Additionally, the Democratic primary in Arizona on March 11 allowed Internet voting to those who asked for "digital certificates," which were essentially encrypted Internet ballots. No indication of problems has surfaced in either instance.

Potential flaws: Critics charge that Internet voting could fall victim to hackers, computer illiterate voters and other vulnerabilities.